Baku, oil-rich Azerbaijan’s congested capital, where Asian and European cultures collide

This article appeared in South China Morning Post on June ’24. You can see the original print here.

Azerbaijan is the largest of the three former Soviet Socialist Republics sandwiched between the great Caucasus Mountains and, to the south, Iran and Turkey, and hemmed in by the Black and Caspian seas.

The commercial exploitation of its vast oil reserves, which began in 1871, has helped the country develop faster than its neighbours, Armenia and Georgia.

The largest city – and the national capital since 1920 – Baku stands along the long crescent of the Absheron Peninsula and is known as “the city of winds” because of its exposure to the strong gusts that sweep in off the Caspian Sea.

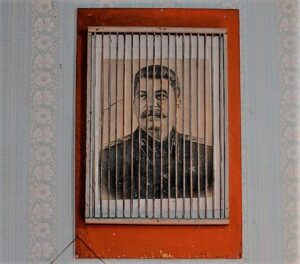

Also blowing over Baku have been the winds of change. Islam arrived from the south in the 7th century with the Arab conquest of the region, which was followed by the Persian and Ottoman empires.

These behemoths battled for dominance and control in the Caucasus until a third great power, Tsarist Russia, muscled in from the north, taking complete control in 1828.

All of this history is reflected in the architecture of Baku.

Take a walk on the cobblestones of the Old Walled City (Icherisheher, or “Inner City”) and you’ll pass the hammams, mosques, teahouses, caravanserais and sunken gardens that made Baku an important stop on the Old Silk Road.

At the top of the walled city is the Palace of the Shirvanshahs, a confusing jumble of austere sandstone buildings that now houses a museum containing a collection of coins, copper utensils, costumery and carpets, decorations, musical instruments and weapons.

Closer to the sea is the other iconic Icherisheher monument, known as the Maiden Tower. Possibly dating back as far as 600BC, nobody knows for sure why it was built, but visitors can climb to the top for a great view of Baku Bay and the walled city.

Step outside the walls of the Icherisheher and it is like being catapulted from ancient Asia into recent Europe.

In the late 19th century, newly rich immigrants from Germany, Greece, Poland and other European nations competed to build ever more opulent sandstone mansions in gothic, baroque, neoclassical and other renaissance styles, with Baku becoming known as the Paris of the Caucasus in the process.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union, in 1991, Azerbaijan emerged for the first time as a free and independent nation state. And the architectural landscape changed yet again, to reflect this feeling of liberation.

The foremost icon of the new Azerbaijan is the giant white Heydar Aliyev Centre, which stands proudly in the heart of Baku as its cultural hub. People see what they want to see in the building, but to me, with its flowing lines and soaring glass panes, it seems like a fantastical sea creature stranded on a vast green beach.

Another new, skyline-defining architectural project is the Flame Towers, a trio of skyscrapers whose innovative design is meant as a tribute to Azerbaijan’s motto, the Land of Fire.

Conceptualised as giant flames leaping from the ground, the towers soar to a height of 190 metres (623ft) and are covered in LED screens that create an awe-inspiring light show at night.

Beachgoers in Baku have a choice of where to spread their towels, with the most popular being Shikhov Beach, 9.5km (6 miles) south of the city centre. An aqua park and swimming pools are an added attraction here for those wary of water pollution.

Less polluted, and about 30 minutes by car northeast of Baku, is Bilgah Beach. Admission is free but there’s a small fee to use the changing rooms, umbrellas and sunbeds.

Baku’s beaches tend to come lined with restaurants serving delicious fish kebabs.

Tea drinking is an important facet of Azerbaijani culture, so a chaykhana (teahouse) is an essential part of any visit to the country.

The chaykhana tea ceremony is a cultural experience wherein you sit cross-legged on cushions at low tables while tea is poured into traditional pear-shaped glasses and often spiced with cinnamon, cardamom leaves, lemon or ginger, and served with a variety of jams and sweets.

Downsides to Baku

Despite hosting a Formula One Grand Prix (September 13 to 15, this year), Baku’s traffic situation offers anything but a smooth ride.

Since gaining independence, Azerbaijan’s population has surged from 7 million to 10 million, with a substantial number of these extra people settling in the capital.

Together with the emergence of Baku as an economic hub and rising prosperity for its citizens, the demographic shift has caused the number of private vehicles to skyrocket.

A lack of investment in public transport exacerbates the problem, leaving visitors with little choice but to rely on taxis (Uber and Bolt also operate in Baku) or hire cars to get around the city. Be prepared for frustrating delays in traffic around the inner city.

The cost of accommodation can be a significant deterrent for budget-conscious tourists or those visiting with a family (a standard room at a Hilton, Hyatt or Marriott is in the US$100 to US$150 a night range, although rooms for less than US$100 a night can be found in smaller establishments).

Many Azerbaijani citizens prefer to holiday abroad rather than in their own country for this reason.

With Dubai seen as a model for tourism development, there has been little focus on the affordable end of the market by the state tourism agency.

Also, the fact that more than half of all Azerbaijan’s hotel rooms are in the capital has not encouraged tourism to spread to places such as Sheki – 250km to the northwest and the country’s self-proclaimed hub for arts and crafts – which only exacerbates demand in Baku.

Pollution problems

For tourists, the beauty and biodiversity of the Caspian Sea have always been significant attractions. However, the dumping of industrial and domestic sewage, often untreated, into the sea has led to severe degradation in water quality and the temporary closures of beaches for swimming in areas such as Shikhov, Sahil and Hovsan.

Furthermore, oil extraction dating back to the Soviet era has had a lasting impact on the Caspian Sea’s ecology. Modern wells may adhere to stricter environmental standards, but old wells continue to leak significant amounts of oil, further polluting the sea.

![]()