Riding The Wild Brahmaputra

This article first appeared in print on March 2, 2003 in the Travel Section of the New York Times with the headline: RIDING THE WILD BRAHMAPUTRA. You can check out the original article here.

It happened in an instant. One second we were riding a huge wave on the Brahmaputra River, our raft angled sharply upward. The next we were poised at its crest over a huge hole, and a huge diagonal wave exploded into us, flinging us into the maelstrom of white water.

I plunged into its icy green depths, suddenly alone in the grip of a force of nature over which I had no control. I was hurled along like a rag doll, the paddle still stuck in my clenched fist.

After what seemed an eternity (but was probably only seconds), I saw a familiar orange shape looming in my watery vision. Pete, one of the safety kayakers who had been hovering downstream in case of a mishap, came to my rescue, and I clung gratefully to the back of his boat as he towed me to shore. I collapsed on the rocky beach, my breath coming in ragged gulps, still not able to believe what I had just been through.

This huge Class IV (advanced) rapid, named for Ningguing, a village that perches high above it, was the first of the challenges of the mighty Brahmaputra in northeastern India. I was one of 30 clients who had paid to participate in an expedition there in November organized by Aquaterra Adventures of New Delhi. While the river had been run a handful of times before by military-assisted private groups, this was the first big commercial trip, partly sponsored by Paddler Magazine.

The world’s highest and one of its greatest rivers, the Brahmaputra (Son of the Creator) starts its journey as the Zangbo (also spelled Tsangpo) just short of the sacred lake of Mansarovar in western Tibet. Racing across more than 1,000 miles of the Tibetan plateau, it loops back on itself — the Big Bend — before entering Arunachal Pradesh, India’s northeasternmost state.

The Chinese invasion in 1962 across this northeast border has left its legacy in the form of a strong military presence and stringent requirements for visitor permits, which have discouraged casual tourists, so this remains one of India’s most remote regions. Few Indians and even fewer foreigners ever make it up there. Our arduous journey to reach the put-in point at Tuting, 18 miles from the border, had taken us four days and three forms of transport — airplane, a battered old river ferry and finally a convoy of Sumo jeeps that had driven up the mountainous Dihang — or Siang, as it known locally –Valley.

We left New Delhi on Nov. 22, flying to Dibrugarh, the district headquarters of Upper Assam state. The next day, we loaded our equipment and provisions onto the river ferry and chugged upriver to Oriam Ghat, an eight-hour journey.

Over the next two days, we covered about 185 miles by road in the jeeps, staying overnight in the hamlet of Jengging. And now we were raring to tackle the Dihang, or Great River, as the Brahmaputra is called in its upper reaches — a thrilling whitewater journey that in eight days would take us 110 miles downstream back to Pasiighat.

We were an international bunch with seven Welsh and three American kayakers, a Canadian chopper pilot, an Austrian journalist and two dozen Indians all united by a common love of adventure. The foreign kayakers, who made the trip in their own individual kayaks, had a wealth of experience, having done rivers as diverse as the Mekong, the Gilgit and the Zambezi. Most of the Indians, including me, also had a fair bit of experience on the big rivers of North India, like the Ganges, the Alaknanda and the Bhagirathi, but there were a couple of first-timers. The team was led by Vaibhav Kala, the affable founder of Aquaterra, supported by five river guides and eight logistics and support staff.

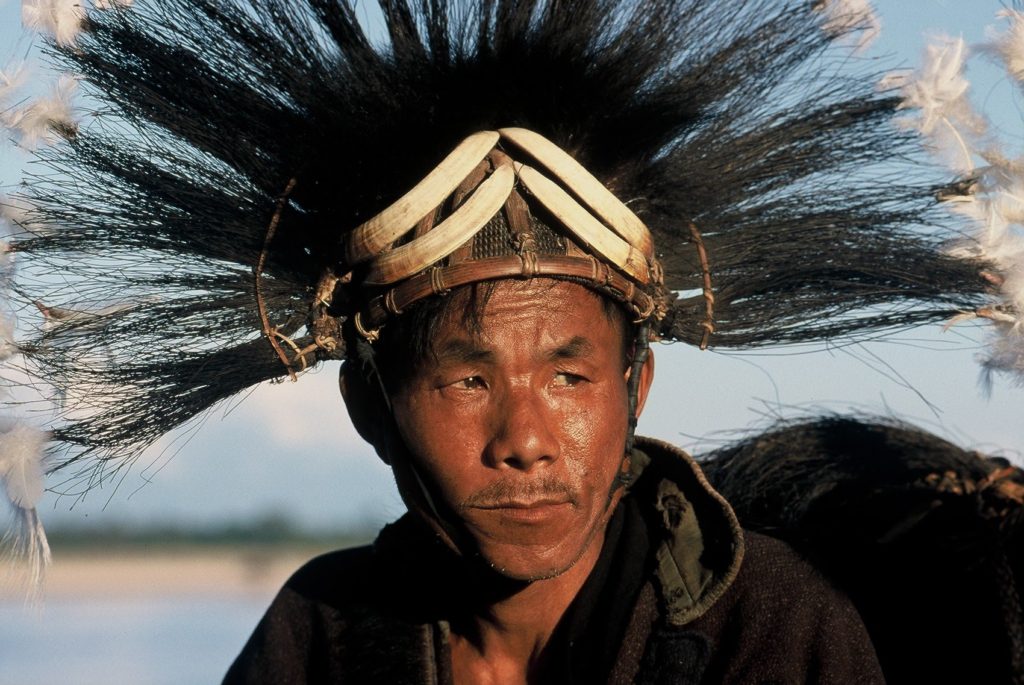

One of the major attractions of the trip was that the Dihang Valley is home to a fascinating tribe of hill people called the Adi, numbering just over 100,000, who still preserve their ancient customs and traditions. We were able to meet them at several welcome receptions and dances organized by the Arunachal Pradesh government. At every major stop, long lines of tribal women in gaily colored skirts, chanting and swaying, greeted our group, making us feel like minor royalty.

On the second day of our road trip, we visited the village of Riga, a cluster of about 50 thatched huts on wooden stilts. The huts were packed closely together, hemmed in by the dense jungle foliage that blanketed the surrounding hillsides. A few palm trees soared above the huts like leafy sentinels, while far below, we could hear the endless roar of the unseen Dihang.

The people who crowded around us had smooth skin and oriental features, looking more like Southeast Asians than like any other Indians I had ever met. An old woman gleefully showed us how to pound rice chaff with our bare feet; later it would be brewed into Apong, a potent rice beer. The wizened village headman, the gam, made a grand appearance in full battle regalia: a helmet made of cane rings, bark loincloth, a longbow and a quiver of poisoned arrows.

He gave me his sword belt to try on and I unsheathed his dao with a careless flourish that almost decapitated him. The crowd erupted with laughter.

As fascinating as our encounters with the Adi were, our actual river journey was clearly the main attraction. At the end of our first day on the water, we huddled around the glowing campfire, cupping warm mugs of rum in our hands, and reflected on the immense power of the Dihang. Two of our four rafts had flipped at Ningguing and two in the Palsi rapid a few hours later. A few of the kayaks rolled over, but were quickly righted.

While no one had been seriously hurt, we were certainly badly shaken up. For many of the rafters in the group, this was their first experience of flipping, and quite an unnerving one in that kind of huge whitewater. But we were exhilarated, too; we had survived an amazing day.

Confronted by the severity of the Dihang’s challenge, the trip’s leaders decided on a change in strategy. The next day D. Paul (Skinny) Jones, the leader of the Welsh kayakers, and Rico and Jed, the two young American kayakers, left early to scout the Marmong gorge, which lay ahead of us.

The rest of us took advantage of this unexpected break to loll around and recover our spirits. Each of us had been assigned to a two- or three-man tent, which we would pitch at the end of each day’s rafting and roll up the next morning. The communal meeting point was the dining place, —- a tent convering strung on four bamboo poles — where the chefs spoiled us with a selection of delicious Indian food — rice, lentils, fried eggplant and chicken curry. Often, this would be varied with Western fare like pasta and baked beans; one day we even had homemade pizza.

We called our temporary camp Pango, after a nearby village. With its row of orange and gray Rapeede tents nestled together on a crescent of white sand, it was an idyllic spot. I hade never seen such a profusion of wild vegetation. Giant plantains loomed out of the mist like ghostly green spiders, their leafy tendrils drooping to the earth. Others were dotted across the hillside, exploding into view like silent green fireworks from the surrounding forest cover.

Reassured by the scouting expedition, we left early the next morning only to be shaken wide awake by the spray from Class III rapids (the international rating system classifies rapids from Class I, easy, to Class VI, extreme), which guarded the entrance to the gorge. ”Riding the wave train down that big green highway” is what Jed called it.

I lacked his easy nonchalance, but appreciated his mixed metaphors as we lurched and plunged our way through the giant rapids. A shaft of sunlight illuminated our colorful little flotilla — four rafts, nine kayaks and a cataraft (a cross between a catamaran and a raft) — as we entered the gorge. It was a spectacular place: the sheer rock walls towered above us, crowned by the dense forest; graceful little waterfalls plunged from the heights, the kayakers reveling in their glittering spray.

It was easy to imagine that no one had ever been here before. But someone — or something — clearly had. Two hundred feet above the river, the vegetation came to an abrupt end, sliced off in a clean line as if by a dao. This was the high water mark of the flood of June 2000, when a great wall of water swept down from the Himalayas, wiping out people, houses, bridges and the forest. I tried but failed to imagine what that immense force would have been like in the narrow confines of this rocky gorge.

Later that afternoon, we were presented with a chilling reminder. Deep in the heart of the gorge, the river had changed its course and rolled giant boulders about on its bed. It now ran right to left, right across the valley, gathering power and speed until it crashed against a sheer rock wall in an awesome spectacle of turbulent white foam. It was the paddler’s nightmare — a Class VI — certain death for those who would defy it, and we portaged it the next morning.

After the adrenaline rush of those first three days, the rest of the trip was less eventful; the rapids lost some of their intensity, though they were still big enough to warrant a careful line. There were long stretches of calm, and signs of human habitation began to appear again — terraced fields, thatched huts, the occasional mithun — a cross between a bison and a buffalo.

We passed under several spectacular suspension bridges made of cane and bamboo. At the put-in point at Tuting, I ventured across one such precarious construction, my heart in my mouth as it swayed alarmingly above the Dihang racing far below.

Just over a week after we first set out on the river, we rounded the final bend and suddenly we were out of the foothills. The river had flattened out into an immense expanse of green, the surging rapids of the Dihang left behind. Its powerful flow carried us forward to a waiting reception committee of officials and local people that the state government had organized at Pasighat, our landing point. Our wild and crazy ride was over.

![]()