Visiting Kakadu National Park: The Greatest Aboriginal Homeland

Earlier this year, I was invited as part of an Indian media group to participate in the Australian Tourism Exchange, held in Brisbane in April–May 2025. Now Australia is half a world away, so my wife Saroj and I decided to add on two additional weeks and do some personal exploration.

At the top of our list was to gain a better understanding of Australia’s long and deep Aboriginal history, a complex issue that the country has still not come to terms with. The Aboriginal population, estimated at 750,000 and spread over 400 tribes , at the time of Captain Cook’s discovery were the original inhabitants of the continent. They were almost wiped out when the white settlers arrived in 1788 through a combination of bloody suppression (direct) and the spreading of fatal diseases (indirect). Now their population has recovered to about one million, and the various tribes are being given more land, and accorded recognition and respect, but the process remains fractious and incomplete.

Darwin is the gateway to Kakadu

The first Aborigines migrated to Australia from Southeast Asia via land bridges and water crossings and were hunter-gatherers with a nomadic way of life. The only traces of their existence can be found in the extensive sites of rock art located all around Australia. Of these sites, the Kakadu National Park, a protected area and a UNESCO World Heritage Site, in the Northern Territory, is particularly famous.

The only problem is that Kakadu is a long way away from anywhere – first you have to take a 4.5-hour flight to Darwin from Sydney and then drive 3.5 hours to KNP along the Arnhem Highway. But we were very keen, so we stayed overnight in Darwin, the tropical gateway to the Northern Territory, and then made the drive to Kakadu the next day, keeping a sharp lookout for wallabies along the deserted highway. We checked into the Mercure Kakadu Crocodile Hotel in Jabiru, uniquely designed in the shape of a giant saltwater crocodile, and made our first foray out to Ubirr, the first major site of Aboriginal rock art, to see the sunset.

Stunning sunset at Ubirr

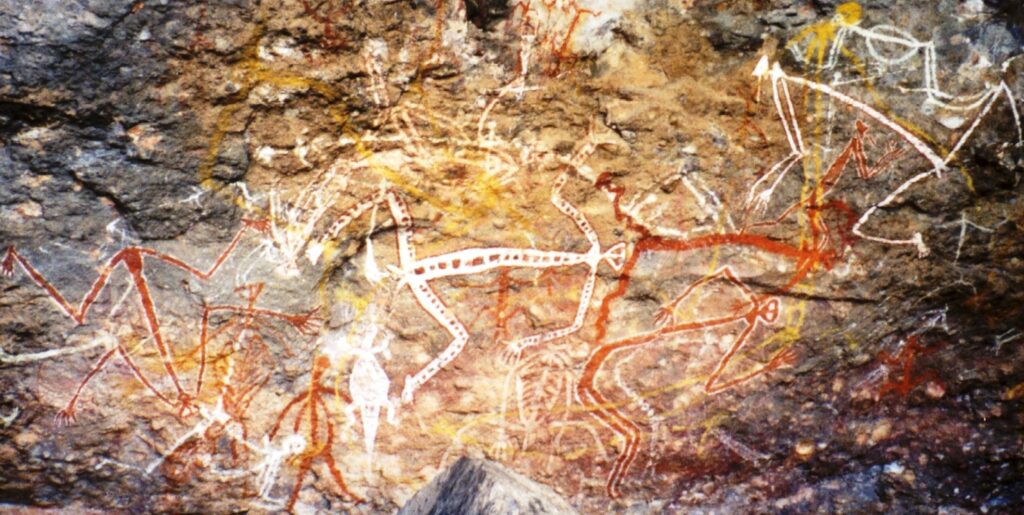

At Ubirr, the trail winds through the darkening forest and we pass sandstone outcrops and shallow caves where ochre figures come to life on the rock walls. The earliest paintings, the Dynamic Figure rock paintings of Arnhem Land, show elongated dancers and hunters in motion, alive with ritualistic energy. Further along are drawings of animals that sustained generations — barramundi, long-necked turtles, goannas, wallabies — rendered in the x-ray style that shows both flesh and skeleton, as though to reveal the inner essence of each being. They serve as both hunting guides and spiritual lessons, reminders of the intimate bond between people and Country .

The final ascent brings us above the galleries to a broad sandstone platform. Suddenly, the world opens out: a sweep of floodplains and wetlands, stretching toward the Arnhem Land escarpment in the distance. The sun is setting in a blaze of glory over fields of green that stretch to the horizon while a herd of buffalo graze peacefully among billabongs that mirror the golden sky. The motley group of tourists fall into a hush as the light fades, and I am deeply aware of standing in a place layered with tens of thousands of years of human presence.

Fascinating rock art at Burrungkuy

The next day, we drive south from Jabiru along the Kakadu Highway until we reach the second major rock art site of Burrungkuy (Nourlangie Rock), which emerges from the Anbangbang Billabong. Here the track winds quietly through open woodland where the light filters gently through stringybarks (a eucalyptus species) and bloodwoods, and the air hums with the rhythm of cicadas. The sandstone mass of the Anbangbang Rock Shelter rises ahead, its face carved by millennia of wind, rain, and bright sunlight. As you approach the first rock shelters, the sense of anticipation grows: the caves are cool and shaded, and on their walls are stories rendered in ochre, clay, and charcoal. One overhang shelters the mythical figure of Namarrkon, the Lightning Man, a creation ancestor whose thunderbolts and lightning announce the coming of the monsoon. Elsewhere, the great Rainbow Serpent winds across the stone, embodying the very act of creation and the shaping of rivers and gorges.

1

On the way back, you can stop at the Nawurlandja lookout to see the most recent phase of contact art in which the Aboriginal artists depicted the sleek wooden sailing vessels (called prau) of the Macassan fishermen who sailed from Makassar in southern Sulawesi in Indonesia to the coastline of northern Australia from the 1700s, followed by top-hatted Europeans and their guns, vivid reminders of first encounters.

The Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Centre

Another 45 km further south we reach the Cooinda Lodge where we have lunch before paying a visit to the Warradjan Aboriginal Cultural Centre. Shaped like a pig-nosed turtle (warradjan), the building draws you into a space where the Bininj people (in the north) and the Mungguy people (in the south) share their own stories. Inside, one moves along exhibits that show how Aboriginal people have lived in spiritual harmony with the land for tens of thousands of years — hunting, weaving, fishing, and reading the six distinct Kakadu seasons. Artefacts, photographs, and recorded voices reveal details of not just daily life but also the spiritual threads of ritual, ceremony, kinship, and ancestral law. I find it to be a deeply meaningful experience which feels less like visiting a museum and more like an invitation to see Kakadu through new eyes, as a living cultural landscape layered with meaning. Not all are equally affected or moved by the experience; a group tour of elderly white Australians who enter after us pass quickly through without so much as breaking their stride.

Night cruise on the Yellow Water Billabong

That feeling of spiritual connection deepens when one steps onto the Yellow Water Billabong for a night cruise. By day the floodplain is a stage for crocodiles, jabirus, and whistling kites, but at night the atmosphere is transformed. In the dry season, the stars blaze across the sky in dazzling clarity, mirrored in the dark surface of the water so that it feels as if you are gliding between two universes. Our guide pauses the boat’s motor and invites us to look up, tracing with a torch beam the outline of the Emu in the Sky along the dark dust lanes of the Milky Way — a celestial bird whose appearance marks the time to gather emu eggs. He also points out the Southern Cross constellation, not just a navigational marker but also a story-anchor linking sky and land. Hearing these stories in place, while buffalo eyes gleam along the banks and the Milky Way arches overhead, turns the cruise into something more than a wildlife encounter. It becomes an immersion into the way Aboriginal people see Country : where land, water, and stars are inseparably woven into one vast, ongoing story.

The stone cathedral of Jim Jim Falls

Our last visit is to Jim Jim Falls, a plunge waterfall on the Jim Jim Creek, which is a sacred Aboriginal site. Traversing the 65-km one-way journey in from the Kakadu Highway is half the experience. The rough, 4WD-worthy track winds through savanna woodlands before ending in a scramble across sun-warmed boulders. At the end of it, the cliffs surrounding the gorge rise like a stone cathedral, sheer sandstone walls enclosing a vast plunge pool. The 200-metre-high waterfall itself is now reduced to a fine thread, a ghost of its wet-season glory , yet the scale and silence of the place feel immense. I wade into the cool, still water, conscious that for the Bininj/Mungguy people, the Traditional Owners of Kakadu, this is far more than a swimming hole. In their understanding, waterholes like Jim Jim Falls are storied places, shaped by creation ancestors whose presence lingers in the cliffs and in the currents. These sites are living repositories of ancestral law and creation stories, teaching people how to move through and care for Country . The water itself is precious. In the parched months of the dry season, such permanent pools sustain generations, drawing animals and people alike. To swim here is to step into a source of life and spirit, not merely a tourist achievement.

Images courtesy of Parks Australia.

![]()

I loved this article, Ranjan. As much as visitors are drawn to Kakadu for the spectacular landscape, flora and fauna, it is the rich culture of the Aboriginal people, who have lived in the area for over 65,000 years, that is the star attraction. Like most good things, Kakadu takes a little time and a sense of curiosity to fully appreciate the destination, and you did exactly that. I’m sure the Bininj would have said to you “kaluk nan”, which means in the local language, “see you later”.

Thank you so much Peter ! It means more than I can say in words that you as a representative of Kakadu National Park should say such kind things about my writing. Perhaps it is because in India we are immersed in a rich multi-cultural society that also goes back thousands of years that gives me a better perspective and understanding with which to view the Aboriginal people of Australia. What I can say is that I just felt a sense of awe and wonder when I was there and would love to come back one day to explore the Park in more depth and with more leisure than we had this first time around.